I can hardly believe that we are approaching the end of 2019—I feel as if I am only just getting myself established in the year and it is already ending.

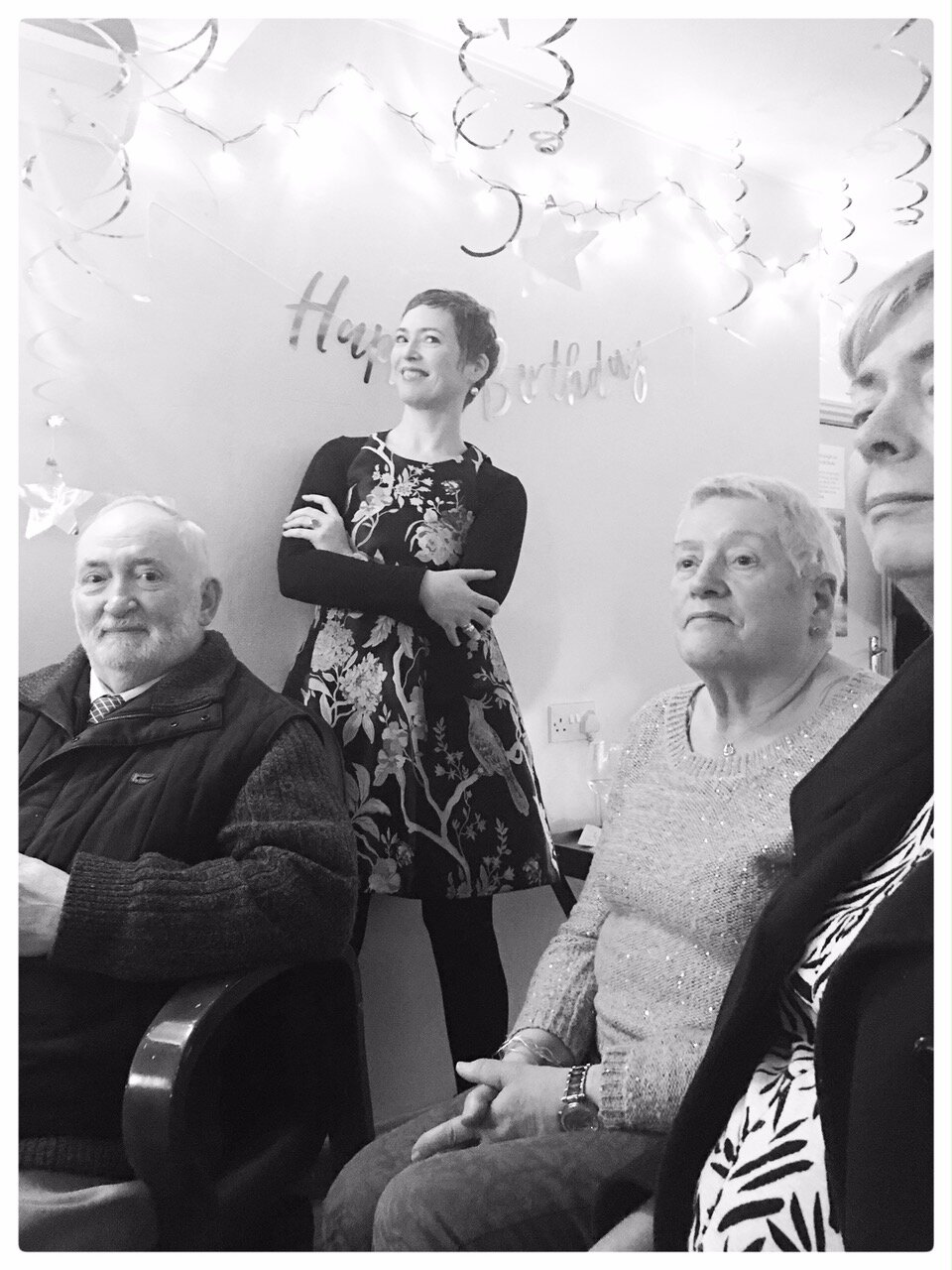

The end of year has been wonderful with a great surprise birthday party for my Mum last weekend—she says it was one of the best parties of her life! Can’t get a better review than that! Some folks asked whether it was her 75th and when I said it was her 74th there seemed some surprise; why not wait until “the big one” to throw a lavish party. But I ask, “why wait?” Tell and show the ones you love how much they mean and celebrate the great relationships in your life as often as possible. I felt all the more adamant of that this year because things didn’t start out as well …

The year got off to a rocky start because I spent New Year’s Eve in the emergency room with my Dad. My Mum and I left the hospital at about 2:30am January 1stand my poor father had to sleep on a trolley in the emergency room. Thankfully he was brought to a bed in the hospital proper in the late morning, but unfortunately he spent most of January in hospital. I had planned a number of things for the early new year: some quality time away with my partner (now husband), some retreat time for myself, some special New Year’s workshops at the studio. All that was scrapped because of my Dad’s illness as my Mom also has some health issues and so I moved in with her while Dad was in hospital. The whole month was a lesson in letting go. I had planned a silent self-retreat to re-immerse myself in the practice of dharma (or so I thought) but the universe decided to send some off the mat/off the cushion dharma practice; what do you do when things go completely another way and you don’t get what you want and there’s no opting out? Then where’s your compassion and lovingkindness and equanimity and joy? Sitting on a cushion in silent retreat can be a luxury in comparison to some of the real life intense yoga and dharma practice that we are offered in our relationships, family and work lives.

This episode was another reminder that how plans can be helpful but it is essential to remember that planning is a strategy that we have come up with to organize reality, but plans are entirely projection; they are not reality—reality will do as reality does—my dharma teacher Eugene Cash used to say “reality is completely wild,” meaning we do not get to control it. It is our job to meet this wild reality and respond wisely. Of course we can grieve the loss of our plans—that’s a true acknowledgement of how we feel about how things are unfolding, but we must stay with reality and not try to hold onto plans which are NEVER reality. Even the most righteous plan, the most well-laid plan, the most practical plans are, when you really examine it, just wishful thinking. I am not suggesting we abandon planning, but that we just know what we are doing. We must remember that we get to concoct them but we do not get to FORCE them into being. Things may go loosely according to plan, they may unfold very close to what we had imagined, but they also must veer wildly off in another direction and in that latter scenario we must remain mindful of the unreality of plans so that we do not fall into the trap of looking for where to lay blame. Blame is usually our first port of call when things do not go according to plans—whose fault is this? Did I mess up? Did someone else mess things up for me? This is what the Buddha called the second arrow. The first arrow is the suffering of things not going to plan and the second arrow if the suffering we create with blame, of ourselves or others. So plans must be seen for what they are, useful tools so long as we remember their unreality. Even though I know all of this intellectually, and have experienced the difficulty of this in life before, this year was another lesson. It was a lesson in thinking you know the lesson and realising, to quote my teacher Eugene again, there’s always more to learn. It seems that what we know intellectually is so often not clear to us emotionally.

Regarding the upheavals early in the year, I performed well on the outside, making relatively wise choices about what to do, but I have to admit there was a lingering sense of “this isn’t fair” and while admitting that isn’t pleasing to my ego (I am a yoga teacher—where is my acceptance and wisdom?), the fact is that when there is an inner complainer, it means that some part of you isn’t getting the nourishment that it needs and it’s acting up. That inner “I’m not getting what I need” was what I was negotiating each day. Of course you could say, but your parents were dealing with health issues and you’re complaining, that’s childish and selfish—just do what you need to do to help and get over yourself. But in my experience, trying to “shut-up” that inner plaintive voice with rationality and logic isn’t terribly helpful. You might “get over it” in a superficial way, but inside resentment builds. And these unprocessed needs or “holdings” live in the body as tension and dis-ease.

So what can we do when we are feeling that our needs are not being met but we do actually have to continue to sacrifice these needs in the short to medium term to be at the service of others? What is extraordinarily helpful is metta; meeting that inner suffering with lovingkindness, holding your disappointment and fear (that you won’t get your needs met) with compassion and tenderness. Then the difficult feelings can be held gently and nourished with lovingkindness, they do not get to dominate the inner landscape and we can then actually recruit the wisdom and strength we need to show up for those who need our help on the outside. Yet another reminder how the inner work of lovingkindness is not selfish or indulgent—it is the cause and condition for us serving others. If you want to love your family and friends in your actions, then you must love yourself because wise actions grow out of wise intentions and it is very hard to sustainably have the intention to care for others if you are not feeling nourished and cared for yourself. Thankfully, my Dad is recovered and doing well, but it took a many months of ups and downs. My Mom has some health issues of her own, but is basically very well. We are doing everything we can to really enjoy the good times (like surprise parties), and support one another when times are difficult. This, as the dharma tells us, is the weave of life, Sukkha (happiness) and Dukkha (difficulty) woven inextricably together.

***

Like every family, we are meeting the three characteristics of reality; difficulty (dukkha), impermanence (anicca), and interconnection (anatta) and working towards the appropriate response. The reality of aging is that things become challenging physically and emotionally. There’s sickness and there are a series of losses and the process of grieving that naturally accompanies these losses is important. We lose careers, and friends, and abilities and each of these stages has to be seen and felt and released if we are not to grow bitter and scared and miss the real opportunities of aging to savour a life well-lived. I often think of what my first teacher Katchie Ananda told us in the first training I did with her—that yoga is the art of dying. It seemed very weird, but actually it makes sense. Yoga is the art of letting go; letting go of our insistence on getting what we want as the measure of happiness, letting go of thinking we can control, letting go of the past, letting go of the future, being fully present in each moment learning what it is to live wisely and coming to know with our whole body heart mind that we are interconnected with all things in this universe. In this way, when it is time for the final letting go, letting go is not a problem, it is what we have been doing all along; letting go is not laced with recriminations and dread, but comes with curiosity and readiness for the next part of the adventure. This is the theory—we all get to explore the practice. The essence of yoga, the art of letting go into reality is indeed a hard practice. But as Katchie used to say, “what else is there to do?” Life is filled with the 10,000 sorrows and the 10,000 joys. What else is there to do but learn how to navigate the swings and roundabouts with wisdom, hold the difficulties with compassion and savour the delights with joy.

***

Perhaps because of the rocky start, It has been a year of trying to keep up with myself and in the earlier part of the year, I found myself answering many polite inquiries into my well-being with “I am very busy these days” and the latter part of the year examining this sense of my reality and renegotiating what it meant to feel it, say it, and act from this stressful state. It was another year of trying to apply a central tenet of yoga practice, the balance of effort and ease, in my relationships, my business operations and my personal practice. It has been yet another year of seeing how what we learn in the yoga practice means nothing unless we apply it to our experience off the mat. I used to think of formal yoga practice (movement, breathwork, meditation, study) and informal practice (what happens off the mat/chair/cushion in relationships with partners, family, friends, work), but increasingly I think it’s all yoga. It’s always about finding connection, staying clear about our intention(s), looking for how to engage in all aspects of experience with a basic friendliness (or at least a lack of hostility), a trust in our ability to connect with wisdom, and live through the appropriate response whether that be Joy or Compassion or some combination of both.

Why did I change from “I’m so busy” to “Life is Full”? On the one hand, “busy” felt true—there always seemed to be something that I “should” be taking care of; but on the other hand as I listened to myself saying it, I started to feel that I was reinforcing the sense of push and pull on myself by constantly defining myself as being in a state of busyness. I started to see how I was boxing myself in, I was creating a whole host of “jobs” that I “should” be doing and of course this ever-expanding to-do list is never exhausted and so there was a sense of failure accompanying the experience. It was exhausting. Thankfully I am learning AGAIN (remember the part about the lesson being that we have not fully learned the lesson) how to rest.

When my teacher Katchie visited us in Sligo in September (a HUGE success and she’ll be back next year), she had powerful message regarding our innocent little creature bodies. If you cannot meet your body with Love, at least try to meet your body with respect. Another teacher of mine, Pascal Auclair used to recommend starting our practice by asking “How are you my love?” to oneself. Recognising that speaking to oneself in this profoundly appreciative way can be a big leap for some, I now suggest asking “how are you my friend?” Sometimes we have to make things more accessible and that’s fine. It’s like modifying a yoga pose—trying less intimidating ways into to a posture, or a contemplative inquiry is not “less than”—it’s the wisdom of meeting yourself where you are and offering the appropriate response.

***

I have been thinking a lot lately about the word “discipline.” It’s often associated with being tough on oneself and imposing rules and regulations that we don’t really want or enjoy. I think that we are missing something here. The word discipline comes from the word “Disciple” one who is devoted. Not to a particular person, although often the disciple thinks that what he or she is devoted to is the person, but really it is what the person is teaching or representing. There’s a beautiful story in the Buddhist tradition to illustrate this:

The Buddha’s Disciple Ananda was out travelling on a mission for the Buddha. After journeying through the forest, he came to a village where he saw a girl drawing water from a well. Thirsty, he asked her if he might have some water. The girl, who was of the untouchable caste was shocked at this request. She said, “I cannot give you water for I am too humbly born. I cannot offer anything to you lest you be contaminated by my caste. Ananda, calmly replied, “ I did not ask you for your caste, I asked you if I may share in the water you have to drink.” He delivered his words with a warm smile. This attitude of friendship was new to her as an untouchable, whose fundamental human worthiness had always been denied. Her heart leaped joyfully and she gave Ananda water to drink.

Ananda thanked her and went on his way. But the girl was so captivated by his response to her, his recognition of her dignity as a human being, that she felt drawn to follow him at a distance. She followed him back to the place where the Buddha and his community were staying, observing his behaviour to those he encountered on his way. Upon realizing that Ananda was living with others in this place as a disciple of the Buddha, the girl went to speak with the Buddha and asked “please let me live in the place where Ananda your disciple dwells, so that I may see him often and minister unto him as his servant, for I love Ananda."

The Buddha understood the strength and wisdom of the emotions of her heart and he said: "Pakati, your heart is indeed full of love, but you misunderstand you own feelings. It is not Ananda himself that you love, but rather the kindness you experienced through his actions. Accept then, this kindness which you have seen him practice towards you and towards others, and you too can practice this same kindness unto all others, not just Ananda.”

The Buddha invited Pataki to join his community if she so wished for he welcomed all people into his community of disciples regardless of caste, teaching that the potential for nobility was in the nature of all born into human form and this nobility was recognised in ones intentions and actions and not in the conditions of one’s birth. He told Pakati;

"Blessed are you, Pakati, for though you are from the group known as the untouchables, through your actions you can be a model for noblemen and noble women. You may be of low caste, but even Brahmans may learn a lesson from you. Swerve not from your recognition of the power of kindness, the path of justice and righteousness and you will outshine the royal glory of any Queen on the throne."

The Buddha is pointing to Pakati’s devotion to kindness—she recognized it in Ananda and so she thought she fell in love with Ananda but really she had fallen in love with kindness.

Think about it—has this happened to you? Have you been really taken by someone but actually it was their behaviour, their joyfulness, their generosity, their kindness that captivated you.

My teacher, Pamela Weiss used to say that anything coming from outside you that really resonates in your heart, the words or actions of another person, resonates so because it is vibrating with something that is already alive in you, yearning for recognition and connection. So Pakati recognized and was touched by kindness because it was already alive within her.

This is true for the teachings of the Buddha—we do not know the Buddha, he doesn’t really have much of a personality in the ancient texts; what is presented are the teachings he left behind. So, we do not love the Buddha so much as the teachings he shared and if they resonate with us when we first hear them it is because they are already alive within us, albeit not cultivated. So when we are disciples of the Buddha, we are devoted to the teachings.

Similarly, when we are disciplined with ourselves it is because we are devoted to our own wellbeing and the wellbeing of others, we are devoted to cultivating the potential for awakening to the fullness of our potential for kindness, compassion, joy and wisdom, and we are devoted to this because we know that it is only by cultivating our own capacities that we may be of service to others. We are devoted to sharing peace and happiness with others.

It is useful to remember this understanding of discipline when the tasks of practice seem to be too unsavoury to bear—getting up early to meditate or do yoga, or finding time to do it later in the day when we feel tired and pinched for time. But if we approach consistency and steadiness in our practice of anything (whether it’s playing music or gardening or doing tai chi) with the understanding that it is not discipline as a grim duty, but a devotion to fulfilling our potential, we often find a way of easing into practice.

Perhaps sometimes getting to our mat or cushion feels like the harder interpretation, the whip of disciple because unconsciously (or consciously) we are making the practice harder than it needs to be. For me, I have a habit of trying to do too much, make it more “impressive”. It’s a pattern I have from a child where I wanted to be impressive in school as a way of getting attention and feeling loved. We all have our strategies, often unconscious, and the practice of yoga and mindfulness is to make those patterns conscious so that we can change them when they are causing us harm.

When I realise then that I am trying to “prove” something to myself in my yoga practice, I can make a shift. If I can come back to the remembrance that I am doing practice to cultivate love and kindness, and not to prove that I am good enough, I can relax and do less. This doesn’t mean the practice cannot be a challenge or doesn’t built stamina or strength, but it isn’t a struggle. The seasoned yoga teacher Judith Hanson Laster says we must always stop and make a shift when we meet struggle—if the practice leaves a bad taste in our mouths, we will not return. Embrace challenge but drop struggle. That was the phrase from Judith that got me through the first six months of the year.

And this reminds me of one of the meanings of OM. The lingering on the MMMMM (the anusvara) is like savouring the taste of something sweet, the Yummmmmmof your favourite food. While our yoga might not always taste like this, if we are not left with a sense of lingering sweetness on a fairly regular basis, something is off. Perhaps we are not infusing our discipline with that sense of devotion.

Dharma Teacher and psychotherapist Tara Brach puts is very well when she says our discipline, our dedication, our devotion, should have a strong willingness rather than a strong willfulness to it. However, if we do notice that willfulness, no need for critique, no need to chastise ourselves. Just notice it’s there and inquire—is this adding to or detracting from an overall sense of sweetness and lovingkindness in my practice. No pushing it away, just caring inquiry into why it might be present and if it is not serving, can we release from willfullness into willingness. Maybe some metta is needed. Meeting ourselves, even our willfulness with friendliness and compassion. Meeting ourselves, as Japanese Poet Izumi Shikibu puts it, no part left out.

And on this note, I’ll leave you with another potent teaching I have picked up from Tara Brach that has fuelled the last six months of this year …